PART 1: Molly

“We can only be responsible for ourselves”. This advice has been given to me several times throughout the years. The first by my uncle’s friend regarding my very young nieces. Again, later by a coworker who said, “we can’t fix the world”. Another time by my husband after seeing two young children being screamed and cursed at by a grown woman I perceived to be their caretaker. I was held in place by my husband who prevented me from approaching the woman. I’ve since learned the ability to see other’s pain is called empathy. The desire to do something about it is called compassion. Most human beings have both.

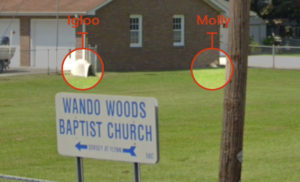

I wasn’t always able to perceive the hurt of others. Perhaps empathy was something I learned however in my 30s I’d become deeply affected and consumed by the perceived suffering of others, especially animals. One such animal was a Labrador Retriever who lived inside a chain link fence on the corner of my street. The dog was confined to the corner lot at the intersections of my road and the main street into the neighborhood. Inside the large grassy, fenced-in lot was one shrub, one neglect-igloo (plastic igloo shaped “dog house”), and Molly, the world’s most beautiful Yellow Labrador Retriever.

Molly’s Corner Lot

Molly in her strip of shade

In my late 30s I moved into a house two doors down from the large corner lot where Molly lived. At that time, I lived with Edie, the world’s most beautiful greyhound. We took morning, midday, and evening walkings, daily. During these walks around my neighborhood, I would have to pass Molly, isolated and alone in her yard. Edie and I’d approach a corner of her fence and be greeted by Molly who’d come trotting over. I’d stop and talk to her, giving her scratches and pets. She’d then accompany us from corner to corner, parking herself at the last corner and bark until I could no longer hear her.

Molly – Photo by Holly Bartley on Unsplash

Each time I passed Molly, I observed her condition. She was a healthy weight though I never saw a bowl of water nor another human interacting with her. She was outside in her yard, rain or shine, day and night through extreme heat from our Lowcountry summers and damp freezing winters. I was painfully aware and disturbed by her isolation and lack of shelter though I knew she was far from the only dog in my neighborhood who lived in isolation and confinement.

Motivated by my past, the fateful day came when I decided to do something for Molly. Edie and I were on our walk, but before approaching her yard, I noticed movement on the far side of her lot. A man was walking from the brick house which was separated from Molly’s yard by a driveway. Molly was at the corner closest to me – opposite her gate. She heard the man approach her gate and turned to see him aim and swing a metal bowl filled with dried kibble into her fence. Pieces soared and fell to the ground. I recognized him as the man who lived in the house. The man who owned Molly. The man who also lived with a white toy poodle and was rarely seen without the poodle. Though it was Molly’s meal time, she didn’t move. She stayed where she was, facing Edie and I.

Dirty Yellow Labrador Retriever

Dirty Yellow Labrador Retriever

This broke my heart even more. The relationship between human and canine has been symbiotic for thousands of years. As two separate but social species who’ve learned to depend on each other’s strengths for protection, companionship, and care. The traditional human/canine dynamic is as follows: food and shelter are provided in exchange of alarm of danger and protection, while both species benefit from companionship. This relationship results in mutual dependence which forms a strong bond of loyalty. Molly was so ignored by the man who provided her care that she didn’t feel drawn to greet him at her gate, not even for food – meaning, in the short time I’d lived nearby, she’d developed a stronger bond to me than to him; proving that touch and connection is as vital to our wellbeing as food and shelter.

I decided then to ignore the advice of so many, including Stephen R. Covey, writer of The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People and step out of my “circle of concern” and into my “circle of influence”, more specifically, I stepped into Molly’s yard.

Dog ownership and “care” is learned behavior,

passed down through generations.

We place dogs inside pins and boxes – 6ft tall and seamless backyard wooden fences left to live their lives confined, never knowing what’s on the other side of their dividers. We attach dogs to 6ft long chains, never allowing them freedom to run, walk, or smell outside of a 12ft diameter. We do this because our parents do this. Molly just happened to be in a very visible location.

Sheltie

Dogs can not speak for themselves and for years I’ve held on to regret for the way my childhood dog was “cared” for. Like dogs, children are creatures of acceptance. I had to accept my childhood condition and that of our dog. I grew up in a home without heat or AC, little food, little comfort. If I was barely getting my needs met, my dog certainly wasn’t. A purebred Shetland Sheepdog, Reagan, deserved better than her lifetime of filth, boredom, and confinement. Though my mother walked her daily, she never had a fence of her own and spent her lifetime either inside our home or at the end of a wire tether – escaping and running away every chance she could until finally being hit and killed by a car. As a child, I knew her quality of life suffered by my mother’s lack of resources, as did my own.

Motivated by my past, the fateful day came when I decided to do something for Molly. Edie and I were on our walk, but before approaching her yard, I noticed movement on the far side of her lot. A man was walking from the brick house which was separated from Molly’s yard by a driveway. Molly was at the corner closest to me – opposite her gate. She heard the man approach her gate and turned to see him aim and swing a metal bowl filled with dried kibble into her fence. Pieces soared and fell to the ground. I recognized him as the man who lived in the house. The man who owned Molly. The man who also lived with a white toy poodle and was rarely seen without the poodle. Though it was Molly’s meal time, she didn’t move. She stayed where she was, facing Edie and I.

Dirty Yellow Labrador Retriever

This broke my heart even more. The relationship between human and canine has been symbiotic for thousands of years. As two separate but social species who’ve learned to depend on each other’s strengths for protection, companionship, and care. The traditional human/canine dynamic is as follows: food and shelter are provided in exchange of alarm of danger and protection, while both species benefit from companionship. This relationship results in mutual dependence which forms a strong bond of loyalty. Molly was so ignored by the man who provided her care that she didn’t feel drawn to greet him at her gate, not even for food – meaning, in the short time I’d lived nearby, she’d developed a stronger bond to me than to him; proving that touch and connection is as vital to our wellbeing as food and shelter.

I decided then to ignore the advice of so many, including Stephen R. Covey, writer of The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People and step out of my “circle of concern” and into my “circle of influence”, more specifically, I stepped into Molly’s yard.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]